Insecure work, whether through zero-hour contracts or through platforms operating within the gig economy, has come under fire in some quarters for driving high levels of worker stress and anxiety. But others point to the flexibility it provides to workers – particularly if they are students or have caring responsibilities – as well as to employers in sectors with fluctuating demand.

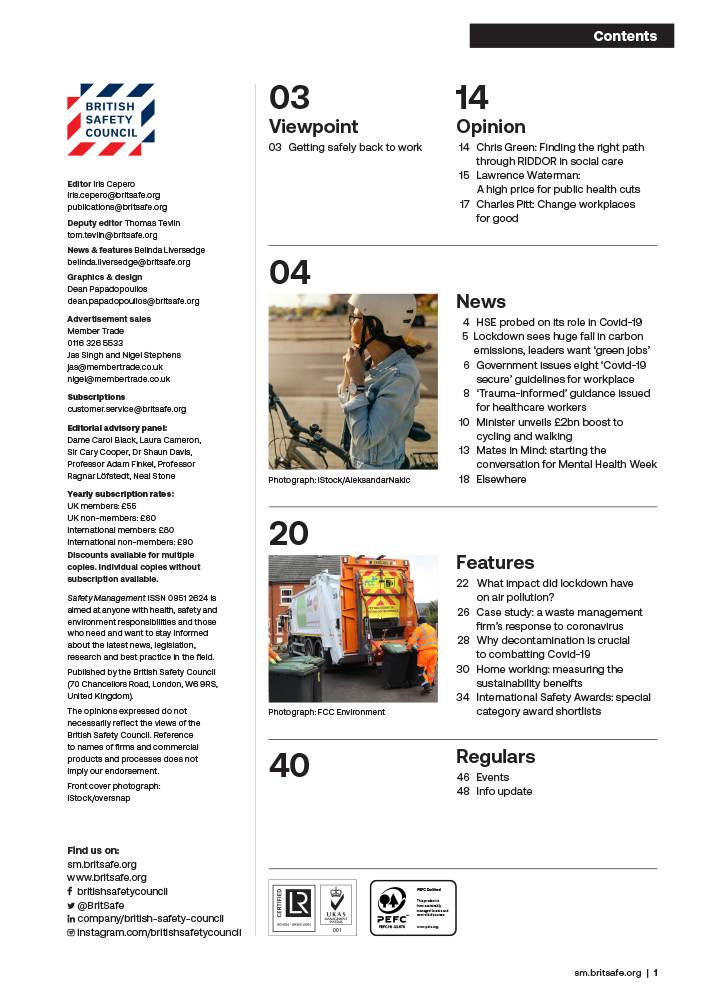

Features

Working in precarious times: the gig economy and zero-hours contracts

Is there a balance to be struck between protecting worker wellbeing and maintaining flexibility? And will the reforms contained in the Government’s new Employment Rights Bill shake things up?

Before attempting to answer either of these questions, it is important to highlight the difference between workers on zero-hours contracts and those who are employed as independent contractors via online platforms. The latter fall into a somewhat grey area whereby they are not necessarily covered by some of the UK’s labour laws.

Photograph: iStock/monkeybusinessimages

Photograph: iStock/monkeybusinessimages

Conflicting court rulings, such as the Supreme Court’s decision in 2021 to award Uber drivers the right to a minimum wage, holiday pay and other benefits, and its decision in 2023 to throw out attempts by Deliveroo riders to unionise, on the basis that they could not be considered employees, demonstrate that things are still very much evolving in the relatively new gig economy.

What platform workers and zero-hours contractors have in common, however, is that they both work on demand, therefore their income fluctuates depending on when their services are required. This, some argue, gives rise to feelings of insecurity, anxiety and lack of control among workers.

“You can think of it in terms of it being employer-driven or worker-controlled flexibility, but, for the worker, it’s really experienced as insecurity,” says Dr Alex Wood, an assistant professor in economic sociology at the University of Cambridge who specialises in researching platform labour and the gig economy.

“So, even if you’re a platform worker and you have the ability to choose when you’re going to work, in reality, you have to work when customers are available or at those times when you’re going to be able to maximise your earnings. So, the flexibility from the worker’s perspective is often a bit of a myth – even if people do value that flexibility, compared to traditional jobs.”

The Supreme Court threw out attempts by Deliveroo riders to unionise, on the basis that they were not employees. Photograph: iStock/MarioGuti

The Supreme Court threw out attempts by Deliveroo riders to unionise, on the basis that they were not employees. Photograph: iStock/MarioGuti

A 2023 study involving 510 UK-based gig workers, led by the University of Bristol and authored by Dr Wood, found that more than three-quarters of respondents said they experienced work-related insecurity and anxiety. More than a quarter of respondents said they felt they were risking their health or safety by performing gig work, while more than half said they were earning below minimum wage.

On the health and safety front, Dr Wood says the risks can be separated into those faced by platform workers who provide delivery and ride-hail services, and those faced by people who provide desk-based services such as graphic design and website programming through online platforms.

The former group, he says, “are under pressure to get good metrics and maximise their earnings, so they’re taking risks when they’re driving on the streets”. However, the latter group also contains “surprising numbers” of workers who say they experience pain as a result of their work.

“That’s because they’re working extremely long hours to tight deadlines, working very intensely and not taking breaks,” he notes.

Gig workers who provide ride-hail services are under pressure to get good metrics. Photograph: iStock/humonia

Gig workers who provide ride-hail services are under pressure to get good metrics. Photograph: iStock/humonia

Both platform work and zero-hours contracts are “very negative for workers”, in Dr Wood’s view: “Both sets of workers have no control over their working time – particularly for zero-hour and short-hour contract workers, who don’t know what their income is going to be week from week or if they’re going to make ends meet. In the case of platform workers, who are paid per job, they need to maximise the number of jobs they’re doing to increase their pay.

“People experience high work intensity and high levels of stress, so you have this combination of anxiety, insecurity and stress, which is obviously very negative for people’s wellbeing.”

Addressing British Safety Council’s 14th Annual Conference on 15 October, TUC general secretary Paul Nowak spoke of what he described as “an epidemic of insecure work”, noting: “One in nine workers work in an insecure contract or no contract at all. A record number of people are on zero-hours contracts and one in five workers doesn’t earn enough to live on.

“When I was growing up on Merseyside in the ‘80s and ‘90s, poverty was a function of being out of work. Now, we’ve got 15 million people living in poverty in Britain – over half of whom are in work.”

But according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), there is “little evidence that employment in the UK is becoming structurally more insecure”, with the proportion of non-permanent employment having remained at about 20 per cent for the last two decades. However, the CIPD states on its website that the UK’s labour market enforcement system is “inadequate” because of its use of individual tribunals.

“This means many workers continue to be treated unfairly and face discrimination as well as difficulties in accessing justice and receiving compensation if their employment rights are breached,” says the CIPD. “There is also a lack of clarity over the issue of employment status and rights, which particularly affects workers in the gig economy.”

Changes to the UK’s three-tier employment model, which contains the three categories of employee, worker and self-employed, would impact the gig economy “far more” than the reforms on zero-hours contracts announced in the new Employment Rights Bill, says Simon Fennell, a partner at Shoosmiths law firm. Such a change, however, “only sits in the [Government’s] ‘Next Steps’ document and we’re simply told there will be consultation with regards to simplifying the employment model”, he adds.

Defining ‘exploitative’

The Employment Rights Bill is more explicit when it comes to zero-hours contracts, promising to ban “exploitative” ones by giving people who work regular hours over a defined period the right to a guaranteed-hours contract, while allowing those who prefer to remain in zero-hours agreements to do so. However, the lack of a clear definition of what is deemed “exploitative” could create issues, according to Fennell, as could the possibility of knock-on effects for other workers if some are granted guaranteed hours.

“As soon as you get to a situation where an employer has to guarantee a worker a particular set number of hours, the reality is that somebody else has to lose out,” says Fennell. “The side effects could be, potentially, that instead of having lots of people working fewer hours, you’ll have fewer people working more hours. That puts a bigger burden back on the state if more people are unemployed.”

One sector that relies heavily on zero-hours contracts and the flexibility they offer is hospitality. Trade body UK Hospitality says that 17 per cent of workers in the sector are on zero-hours contracts – the highest proportion of any industry – and that research suggests these contracts are the desired way of working for the majority of people who are on them.

17 per cent of hospitality workers are on zero-hours contracts. Photograph: iStock/ponsulak

17 per cent of hospitality workers are on zero-hours contracts. Photograph: iStock/ponsulak

“There will always be people who want flexibility week to week – for example carers who need to manage work around their other commitments or a student who wants to dial up work in the holidays and down during exam time,” says UK Hospitality chief executive Kate Nicholls. “People who need that flexibility, or prefer to work seasonal patterns, must be able to access the flexible employment routes hospitality can offer.”

Nicholls believes the 12-week reference period currently being considered by the Government as the point at which a zero-hours contract worker can request a guaranteed-hours agreement should be longer, to reflect seasonality.

“The reference period, as currently suggested, could oblige an employer to provide the same hours in a low-demand season, if a fixed-term contract offer is based on a 12-week reference period that is over a high-demand period, like summer,” she says. “That scenario would not be a positive outcome for either employer or employee.”

Gig economy loophole

Returning to the topic of the UK’s three-tier employment model, there is an apparent loophole that enables businesses to turn to the gig economy to circumvent both the incoming zero-hours legislation and, in the case of hospitality, the new tip-sharing law that took effect in October.

“It is accurate that the current legislation in respect of tips does not apply to those who are self-employed and, therefore, any business which engages a mix of employees/workers and those who are self-employed can distinguish between the two groups when distributing tips,” explains Fennell from Shoosmiths. “There is nothing which suggests that the position regarding tips will change as a consequence of the Employment Rights Bill.

“Similarly, the changes to the way in which zero-hours contracts are to work under the Bill would not impact the genuinely self-employed.”

One gig economy platform that stands to benefit from this loophole is Temper Works, which supplies labour to businesses in the hospitality, retail and logistics sectors on an independent contractor basis. The Netherlands-based company, which was founded in 2015 and expanded into the UK market in 2022, is keen to emphasise, however, that it provides a “fair and equitable” platform through which independent contractors can find flexible shifts that pay above minimum wage.

“Lots of people, when they think of the words ‘gig economy’, think of people who are not treated right or are in some way being exploited, and Temper was founded to change that,” Alex Rose, general manager of Temper Works’ international business, tells Safety Management. “I think there are some common misconceptions around independent contractor working, and it sits at the heart of our mission to make sure that these people are represented fairly and protected.”

For instance, Temper has set a minimum hourly wage for its contractors of £12, which is above the current National Living Wage of £11.44 per hour for over-21s. Rose says that the average hourly pay for its contractors is above £14. The company also ensures that if a client cancels a shift at short notice, they pay the booked contractor half of what they would have earned. Rose points to Temper’s sick pay policy, whereby if a contractor falls ill and cannot work the company will cover 70 per cent of their historical earnings on the platform for up to a year.

“These are all things that Temper does that we don’t have to do by law. We choose to do it,” he says. Another aspect that differentiates Temper from the zero-hours contract model is that “the people on our platform decide which shifts they apply for, so all the power sits with the person applying for the shift”.

Increased scrutiny

While some platform businesses have secured legal victories when challenged on workers’ rights in the courts – such as Deliveroo riders not being allowed to engage in collective bargaining – other recent cases have gone in the workers’ favour. In early November, an employment tribunal ruled that Bolt drivers are not self-employed contractors, but are instead workers who are entitled to workers’ rights and protection, such as minimum wage and holiday pay, under UK employment law.

Shoosmiths’ Fennell warns that gig economy businesses could face increased scrutiny over the employment status of their workers going forward.

“With the Government so obviously focused on improving the rights of working people, I would not be surprised if there is an increase in the scrutiny of platform businesses, i.e. those which are supplying labour on a self-employed basis. It is entirely possible, if not likely, that individuals working in these businesses and sectors will lead the charge to be the next round of gig economy status cases in the same way as we saw with Uber and Pimlico Plumbers,” says Fennell.

“Businesses will need to ensure that the activities of these individuals and the way that they are supervised is managed very carefully.”

FEATURES

India’s path to net zero: a work in progress

By Orchie Bandyopadhyay on 08 April 2025

India is implementing a variety of clean energy measures to hit its target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2070, including plans to rapidly scale up the generation of nuclear power. However, climate experts say significant finance will be required from developed countries to phase out coal power, accelerate renewables deployment and expand the national electricity grid.

Too hot to handle: early arrival of heatwaves in India sparks calls for action to protect workers and the public

By Orchie Bandyopadhyay on 08 April 2025

Temperatures in India in February 2025 were the hottest since records began over a century ago, prompting warnings the country needs to urgently step up efforts to protect both workers and the general population from the health risks posed by extreme heat and humidity.