Many employers are keen to support the psychological health of their workforce through the provision of different forms of training and employee support services, but it’s vital there’s genuine evidence of the effectiveness of the training and support provided, otherwise the investment will be wasted.

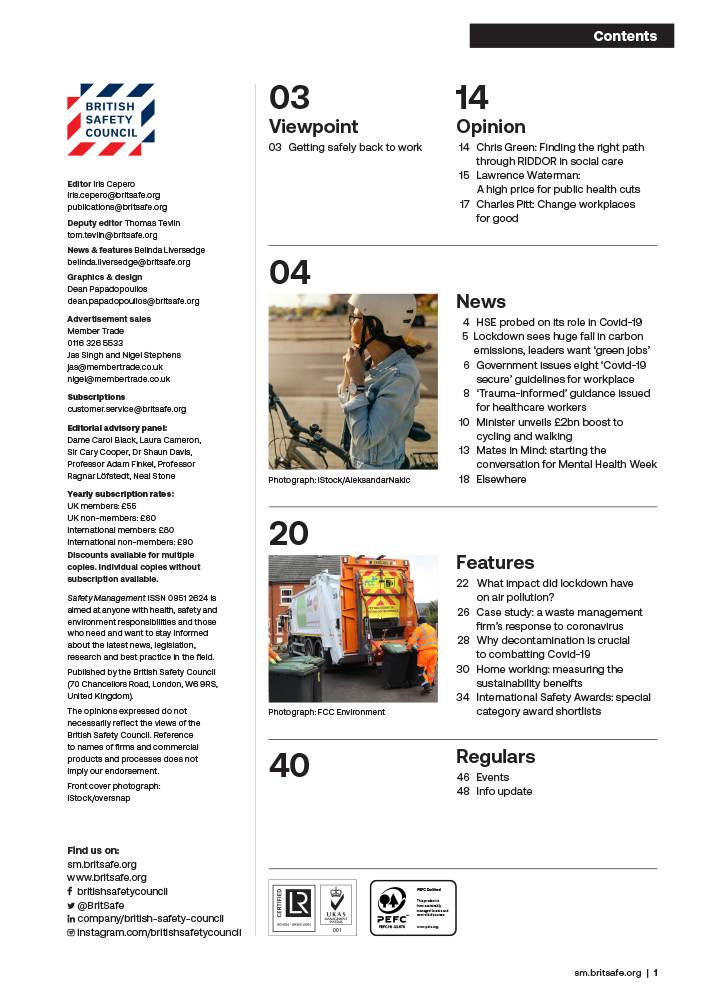

Features

Follow the evidence: how to reap the rewards of effective workplace mental health support training

All employers know that they are obligated to take care of their employees’ mental health, don’t they? Furthermore, the Health and Safety at Work Act tells them this, too. Good employers, of course, will want to support their staff because it’s the right thing to do. However, good AND savvy employers also know that doing so will have a positive effect on their bottom line.

Photograph: iStock/RichVintage

Photograph: iStock/RichVintage

It is perhaps not surprising that there has been an explosion of interest in procuring psychological support options by organisations – big and small, public and private. But in this market, the warning ‘Buyer Beware!’ is particularly pertinent. So, where should buyers of psychological support start?

Duty of care

Well, there are some very well-trodden paths which organisations have taken as they navigate their way along their journey towards some sort of psychologically healthy nirvana which they hope will demonstrate, on the balance of probabilities at least, that they are duly exercising their duty of care towards their staff’s mental health.

For example, employee assistance programmes (EAPs) are plentiful and mental health first aiders (MHFAs) are around almost every corner. However, EAPs are reactive, not proactive and their use by staff is often minimal. For instance, data from the US show that only around five per cent of staff make use of EAPs¹. While MHFA aims to be more proactive than EAPs, evidence of its benefit in the workplace is lacking. For instance, a Health and Safety Executive (HSE) report of 2018 concluded that “there is no evidence that the introduction of MHFA training in workplaces has resulted in sustained actions in those trained, or that it has improved the wider management of mental ill-health”².

But what about the journey to be taken by good employers who know that, rather than being a tick box exercise, mental health support meets their intended outcome(s)? They need to follow the evidence to arrive at the benefits. For instance, some effective workplace interventions may provide an average return on investment of nearly £10 for every £1 spent (Milligan-Saville et al 2017³)?

So, workplace mental health support providers that you should turn to are ones who know that ‘effective’ means evidence-based. For instance, our team at March on Stress regularly make use of, and indeed contribute to the scientific evidence that goes into national⁴, and international⁵, mental health at work guidance.

Assuming then that a good and savvy employer is willing to take the, currently, path less travelled route, by opting for effective workplace mental health training solutions, what evidence-based choices do they have and how do they fit together?

Evidence-based support

At March on Stress, our very core belief is that anyone in psychological distress, whether as a result of exposure to potential trauma or the consequence of other (more day-to-day) occupational stressors, deserves access to the right evidence-based support and care in their workplace. And, in our experience, almost all organisations have champions who share that belief; champions who aren’t interested in simply ‘ticking boxes’.

And when savvy organisations, often embodied by the champions within them, come to our March on Stress team asking to better support staff, we ask them in turn to imagine developing a whole organisation approach depicted by a simplified graphic of a pyramid of psychological support. The pyramid has the following characteristics:

The approaches depicted within the broad, solid base of the pyramid (self-help workshops, enhanced coping skills and mental health awareness), apply to all staff. And of course, that is exactly who good and savvy employers are trying to support – everyone and, in particular, everyone in need.

It is hard to miss ever present media and social media messaging on mental health these days, so among all that ‘noise’, it is valuable for organisations to set out for their staff what the evidence shows is relevant – thus raising awareness of mental health and ill health. The evidence-informed messaging within these briefings should be tailored to the organisation and, ideally, the specific team they are aimed at.

For instance, routinely trauma-exposed teams – such as healthcare staff, emergency responders and media professionals – should be made aware of the impacts of psychological trauma. However, teams of academics, administrators and bankers may need to know less about trauma, but still need to be well aware of ‘routine’ workplace stressors such as demands, control, support, relationships, role and change, which are key HSE (Health and Safety Executive) stress management standards. Such awareness sessions should also detail any organisational support mechanisms and referral pathways open to them and their colleagues.

Professor Neil Greenberg is managing director at March on Stress. Photograph: March on Stress

Professor Neil Greenberg is managing director at March on Stress. Photograph: March on Stress

The sessions may be relatively short (for example, a lunch and learn session) but should provide attendees with an opportunity to ask questions to help them better understand the organisational ethos towards mental health. Organisations may also want to offer specific coping skills training: while it is likely that only a minority of workers will make use of these approaches at a given point in time, it may well be that those who do use such approaches do so at a time of increased psychological need.

Manager training

Moving up the pyramid, we begin to hone in on a slightly narrower group of staff – managers, supervisors and team leaders who have key roles to play in protecting the mental health of staff. This sort of training has the strongest evidence base⁶ of an impact on workers’ mental health. Team cohesion and leadership (at any level) has a profound effect on workplace mental health, and therefore on performance, retention, absenteeism and presenteeism.

So, how might this training have such an impact? First, it makes sense to make sure that everyone who has supervisory responsibilities knows how to – and is not afraid to – recognise where somebody might be struggling and have a conversation about it. This supports the 2022 Mental Health at Work Guidelines from the World Health Organization⁷, which recommends that training for managers to support their workers’ mental health should be delivered to improve managers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviours for mental health and to improve workers’ help-seeking behaviours.

And that conversation must be more meaningful than passing the phone number of the organisation’s EAP across the desk (or worse sending it on email). Being able to have such conversations can help unlock mutually agreed solutions to the problems that are contributing to someone’s stress levels. Sometimes it may be necessary for a highly distressed worker to ‘jump to the top of the pyramid’ (which is where clinically focused support is provided) but, more often than not, an effective, mental health-focused conversation between a worker and their supervisor will uncover solutions that can resolve their difficulties without a need for a professional healthcare-provided intervention.

What is critical is that any mental health training for supervisors involves practising active listening skills so they can have a constructive mental health focused conversation⁸. Evidence suggests that acquiring such skills need not take forever; a few hours can substantially increase a supervisor’s confidence in having such a conversation.

Empathetic leaders

Capable and empathetic leaders and managers who understand their role in supporting the welfare, health and safety of their people can also be trained to facilitate regular group sessions with their teams, either in ‘steady state’ or to reflect on events or periods of time that have been particularly challenging.

Such ‘Reflective Practice’ sessions are story sharing meetings where, without blame, participants are able to share perspective and leave the room a little ‘lighter’ than when they entered. They can be thought of as essential periodic maintenance like oiling a bicycle chain or, put another way, such sessions can help staff to develop a meaningful narrative – a story in which everyone realises that they ‘are in this together’. The evidence for these sorts of approaches is building⁹ and they are likely to be especially useful for staff who have to regularly deal with morally challenging situations to which there is no clear answer.

Peer support

Further up our Psychological Support Pyramid is the building of formal collegial support processes in the form of peer support. We consider that peer support is the mainstay of our pyramid structure which provides a bridge between what all staff and managers should know, and clinical services for the minority who need them.

The most well-known and well-researched peer support programme is TRiM (Trauma Risk Management), which originated in the UK military more than 20 years ago and is now used throughout countless wide-ranging organisations, from health to emergency services, to media to government, to transport and construction.¹º

TRiM is a peer support intervention carried out following potentially traumatic events. TRiM practitioners are peer supporters embedded throughout an organisation who are trained to spot the signs of psychological distress in their colleagues that might otherwise go unnoticed, through a structured risk assessment process which supports an individual during the all-important period of ‘active monitoring’ following a trauma, as recommended by the National Institute for Care and Excellence.

Georgina Godden is business development director at March on Stress. Photograph: March on Stress

Georgina Godden is business development director at March on Stress. Photograph: March on Stress

The research shows that TRiM is highly effective at keeping people functioning at work following a traumatic event, reducing both absenteeism and presenteeism – better for the individuals’ health and the organisation.¹¹

Most people who receive a post-trauma TRiM intervention will have received the necessary (in most cases informal) support they need to move on from the trauma. However, inevitably, an important minority will have been assessed by a TRiM practitioner as needing further help following the period of active monitoring. The aim of early detection is to facilitate better treatment outcomes. While mental healthcare can be effective even after a considerable delay, earlier treatment makes it more likely that people will maintain their key relationships, be able to remain at work and preserve their self-esteem.

Peer support can also be used for more day-to-day occupational stressors – using different evidence-based risk factors but the same principles. Sustaining Resilience at Work (StRAW®) is one such programme, developed using all the evidence gathered from two decades of TRiM interventions.¹²

Sit down and talk

Peer support works, in part, because there is good scientific evidence which shows that most employees who experience intense challenges would rather sit down and chat with a colleague, someone they know understands their job, than with a member of HR, a healthcare professional or even their boss.

It is important to note that peer support programmes, such as TRiM and StRaW, should be very boundaried. Peer support practitioners neither diagnose nor treat and they are definitely not clinicians. Furthermore, peer support programmes also need to consider the welfare of the practitioners who may, if not well supported themselves, become negatively impacted as they hear their colleagues speaking about their woes. However, quite often, the support offered through meeting with a peer support practitioner is enough to help someone on their road to recovery – and to feel good about the organisation they work for at the same time.

So far, then, our pyramid gives us:

- A mental health aware workforce, that understands the pathways to support available to them, so that they can alert a psychologically savvy manager, or another potential source of support, if they, or a colleague, is struggling

- A supervisor who can not only spot the signs of psychological distress, but can have a psychologically informed conversation with a member of their team to move them towards solving their problems or getting some more expert help, which in the first instance could be a referral for a peer support chat

- Peer supporters who can offer an assessment, and the provision of evidence-based informal support, for staff exposed to trauma or significant occupational stress, in order to facilitate positive outcomes or good quality referrals onto more professional services.

This means we have climbed to the top of our Psychological Support Pyramid – where the experts sit. Effective workplace mental health support training makes it more likely that staff who need professional assessment and interventions get them.

Photograph: iStock/laflor

Photograph: iStock/laflor

Such experts should ideally include occupational health (OH) staff. However, some organisations may have other health and wellbeing staff including occupational mental health professionals who can work alongside OH staff. Other organisations may rely on their EAP to provide a first line of psychological support. Others still may rely on the NHS, possibly supplementing their services with private healthcare provision where waiting times are elongated.

What is important, though, is that any mental healthcare provided for staff specifically focuses on helping people stay at or return to work. Unfortunately, mental health treatment that focuses only on symptom reduction is far less likely to help people be at work.¹³ Organisations that recognise the value of helping staff with mental health problems access work-focused care will also be helping to break down stigma, encouraging team members to be more open about their mental health.

Great! But, of course, every organisation is unique isn’t it? One size doesn’t fit all and what might be right for one organisation may not be right for another. What may be easily rolled out to a small or medium-sized enterprise may struggle to gain traction within a more complex structure. Right?

There are differences between organisations, but one benefit of evidence-based workplace mental health training is that it is scaleable and adaptable to your structure, geography, hierarchy, shift patterns and policies. Follow the evidence and, starting with one supervisor, team, department or individual peer supporter, you can build a pathway between your most precious commodity - your people – and those employed to help them.

Professor Neil Greenberg is managing director and Georgina Godden is business development director at March on Stress.

For more information see:

T: +44 (0)2392 706929

References

- Society for Human Resource Management. (2019). Companies seek to boost low usage of employee assistance programs. Retrieved from tinyurl.com/mv7ppdj4

- hse.gov.uk/research/rrhtm/rr1135.htm

- tinyurl.com/bddmzjkw

- nice.org.uk/guidance/ng212

- who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work

- tinyurl.com/mpe7bb6z

- who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053052

- tinyurl.com/4uzn8mym

- bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/10/e024254.abstract

- marchonstress.com/page/p/trim_articles_and_research

- tinyurl.com/bdf2u6wf

- journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2165079919873934

- tinyurl.com/4j2y8y7m

FEATURES

India’s path to net zero: a work in progress

By Orchie Bandyopadhyay on 08 April 2025

India is implementing a variety of clean energy measures to hit its target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2070, including plans to rapidly scale up the generation of nuclear power. However, climate experts say significant finance will be required from developed countries to phase out coal power, accelerate renewables deployment and expand the national electricity grid.

Too hot to handle: early arrival of heatwaves in India sparks calls for action to protect workers and the public

By Orchie Bandyopadhyay on 08 April 2025

Temperatures in India in February 2025 were the hottest since records began over a century ago, prompting warnings the country needs to urgently step up efforts to protect both workers and the general population from the health risks posed by extreme heat and humidity.