Although India has stringent laws banning the employment of children and adolescents in harmful work, millions of children continue to be exploited and put at risk in dangerous jobs and industries.

Features

Child labour in India: a long way to go

From working as child labourers to representing India in a global event by the International Labour Organization (ILO) at Durban, South Africa – the journey has been long for both Badku Marandi and Amar Lal.

A resident of Kanichihar village in the Tisri block of Giridih district in Jharkhand, 21-year-old Badku’s father passed away when he was five. His mother Rajina Kisku and he then started working in a mica (silicate material) mine to eke out a living. In 2012, the mine collapsed during heavy rains, and he was rescued from the debris.

Badku said two persons, including one of his friends, died in the accident while he somehow survived but lost the vision in one of his eyes.

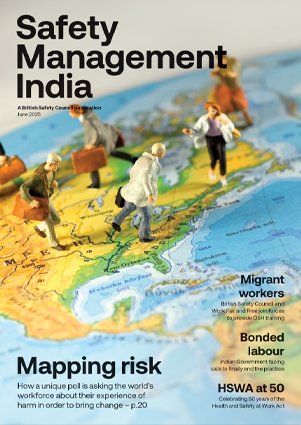

Photograph: iStock, credit Vardhan

Photograph: iStock, credit Vardhan

Although Badku survived the accident, he was shattered by the death of his friend. In 2013, the Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation selected Kanichihar village as a Bal Mitra Gram (BMG) or a child-friendly village, an initiative aimed at protecting children from exploitation and ensuring they receive education. Badku was enrolled in a school the same year and became the first individual in his village to pass the matriculation exam.

He was also elected head of the ‘bal panchayat’ (Children’s Panchayat, or children’s village council), and now works as an active member of the BMG.

Mica mining

Giridih district is rich in mica mineral. Although mica mining was banned in Jharkhand some two decades ago, in the absence of any other source of income, the local Santhal tribal population is completely dependent on mining the mineral to earn its livelihood.

As a result, the tribal people are forced to descend into illegal rat-hole mines to collect mica scrap, which they sell to the middlemen for as low as Rs 5 per kilogramme.

However, there have been incidents where the mines have collapsed, and a number of Santhal families, including young children, have been buried alive. Those who survive working in the mica mines suffer various health problems, including breathing illnesses and even tuberculosis.

After being rescued by the Kailash Satyarthi Foundation, Badaku says his life mission now is to rescue other children and encourage them to begin a new life.

“Working in mica mines was a painful experience and I urge all participants to create a world where no one is bereft of education and happy childhood,” said Badaku at the ILO event in Durban.

Amar’s childhood was very similar. Belonging to the Banjara community in Rajasthan, he worked in a stone quarry with his father at the age of six. Amar was rescued by Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), a voluntary association that works to end child exploitation in India. He was brought to the BBA’s Bal Ashram rehabilitation and training centre for children rescued from child labour, child slavery and child trafficking. This was co-founded by Nobel Peace Laureate Kailash Satyarthi and his wife Sumedha Kailash.

After completing senior secondary education, Amar pursued legal studies in college. Currently, he is working as a children’s rights lawyer and activist.

“Although governments across the globe spend billions on war, pertinent issues, such as health and education of children are placed on the backburner,” said Amar in his address at the ILO event Durban. “To benefit from child-friendly laws and regulations, more efforts are required in their implementation.”

‘10.1 million child labourers in India’

Badku and Amar are the lucky ones but, according to data from the 2011 Census, there are 10.1 million child labourers in India, of which 5.6 million are boys and 4.5 million are girls.

Across India, millions of children are forced into unpaid or paid work that deprives them of an education, a happy childhood and a prosperous future, and they continue to be exploited for cheap labour.

The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 aims to eradicate any kind of child abuse in the form of employment. It prohibits the engagement of children in any kind of hazardous employment, who have not reached 14 years’ of age. The Act also prohibits the employment of children in certain occupations and processes.

Even though the law is strict in its provisions against child labour, the employment of children in harmful and illegal work remains common. The key reasons appear to be a lack of awareness of the law and a lack of implementation and enforcement of the rules by the authorities.

The law on child labour in India

At first glance, the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2016, passed in Parliament, appears progressive. It bans “the engagement of children in all occupations and of adolescents in hazardous occupations and processes”. Adolescents are defined in the Act as those under 18 years and children as those under 14. The Act also gives the authorities the power to fine those who employ or permit adolescents to work.

However, commentators say that, on scrutiny, the Act is inadequate in many ways.

“Firstly, it has slashed the list of hazardous occupations for children from 83 to include just mining, explosives and occupations mentioned in the Factory Act,” says Ruchira Gupta, an anti-trafficking activist and founder of Apne Aap Women Worldwide, an organisation that helps marginalised girls and women to resist and end sex trafficking.

“This translates into [meaning that] work in chemical mixing units, cotton farms, battery recycling units and brick kilns, among others, have been dropped [from the list of hazardous occupations and processes that young people must not do]. Moreover, even the ones listed as hazardous can be removed, according to Section 4 – not by Parliament but by government authorities at their will.”

Gupta adds: “Secondly, section 3 in Clause 5 allows child labour in ‘family or family enterprises’, or allows the child to be ‘an artist in an audio-visual entertainment industry’.

“Since most of India’s child labour is caste-based work, with poor families trapped in intergenerational debt bondage, this refers to most of the country’s child labourers.

“The clause is also dangerous as it does not define the hours of work; it simply states that children may work after school hours or during vacations.

“Think of the plight of a 12-year-old coming home from school and then helping her mother sow umpteen collars on shirts to meet the production deadline of a contractor. When will she do her homework? How will she have the stamina to get up the next morning for school?”

According to the ILO, around 12.9 million Indian children are engaged in work between the ages of seven to 17 years’ old. When children are employed or doing unpaid work, they are less likely to attend school or attend only intermittingly, trapping them in the cycle of poverty. Millions of Indian girls and boys are going to work every day in quarries and factories, or selling cigarettes on the street, for example.

The majority of these children are between 12 and 17 years’ old and work up to 16 hours a day to help their families make ends meet. But child labour in India can start even earlier with an estimated 10.1 million children between the ages of five and 14 years’ old engaged in work.

In fact, data from SOS Children’s Villages, a non-governmental international development organisation that provides humanitarian and developmental assistance to children in need, suggests that in India, 20 per cent of all children aged 15 to 17 years’ old are involved in hazardous industries and jobs.

Photograph: iStock, credit Paresh

Photograph: iStock, credit Paresh

Under-reporting of child labour in India

Measuring the exact scale of child labour in India is difficult as it is often hidden and under-reported. There are almost 18 million children between the ages of seven to 17 years’ old who are considered ‘inactive’ in India, neither in employment nor in school. These missing girls and boys in India are potentially subject to some of the worst forms of child labour.

However, Nobel Laureate Kailash Satyarthi has a different take. Highlighting that India has done “much better” in the fight against child labour under the Narendra Modi government, Satyarthi expressed confidence that the last child in the country would be safe, free, and educated by 2047, when India celebrates 100 years of independence.

Speaking to media persons, Satyarthi said social and political will is needed to end child labour in India and asserted that the government will need the support of society and the private sector.

“The last child in India should be free, safe, educated and given all kinds of protection and opportunities. I’m sure it will happen (before 2047),” said Satyarthi, while in the United States meeting members of President Joe Biden’s administration, think tanks and lawmakers.

Satyarthi was responding to a question on his vision for India when it celebrates 100 years of independence in 2047. In 2022, India is marking its 75th year of independence, which is being celebrated as ‘Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav’ across the globe by people of Indian origin and Indians living overseas.

Satyarthi said the Covid pandemic is not simply a health or economic crisis but a crisis affecting the entire civilization and children are going to be those who suffer the most.

“In fact, they are already the worst sufferers,’ he said. “If we are not able to address their issues with utmost sincerity and urgency, then millions of children may fall into slavery, trafficking child labour. Millions of children will be forced to leave schools.”

According to a new report, the number of children in child labour has risen to 160 million worldwide – an increase of 8.4 million children in the last four years. The report also found that millions more children are at risk of falling victim to child labour due to the impact of Covid-19.

Dr Yasmin Ali Haque, UNICEF India representative, said: “The pandemic has clearly emerged as a child rights crisis, aggravating the risk of child labour as many more families are likely to have fallen into extreme poverty.

“Children in poor and disadvantaged households in India are now at a greater risk of negative coping mechanisms such as dropping out of school and being forced into labour, marriage and even falling victim to trafficking. We are also seeing children lose parents and caregivers to the virus – leaving them destitute, without parental care. These children are at extremely vulnerable to neglect, abuse and exploitation.”

She added: “We must act fast to prevent the Covid-19 pandemic from becoming a lasting crisis for children in India, especially those who are most vulnerable.”

Civil society organisations (CSOs) have been playing a significant role in the elimination of child labour in the Asia and Pacific regions (APR). They contribute towards achieving the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Target 8.7 through the implementation of programmes aimed at preventing and eliminating child labour.

The CSOs work closely with governments, UN agencies and other stakeholders in advancing the legal and policy frameworks of countries in the region towards this end. Many CSOs work directly with children engaged in labour, particularly in rescue, rehabilitation and empowerment programmes. They also ensure child participation in important policy and programmatic initiatives.